The Bengal Guards: Their legacy lives on

Published 8:57 am Saturday, January 30, 2016

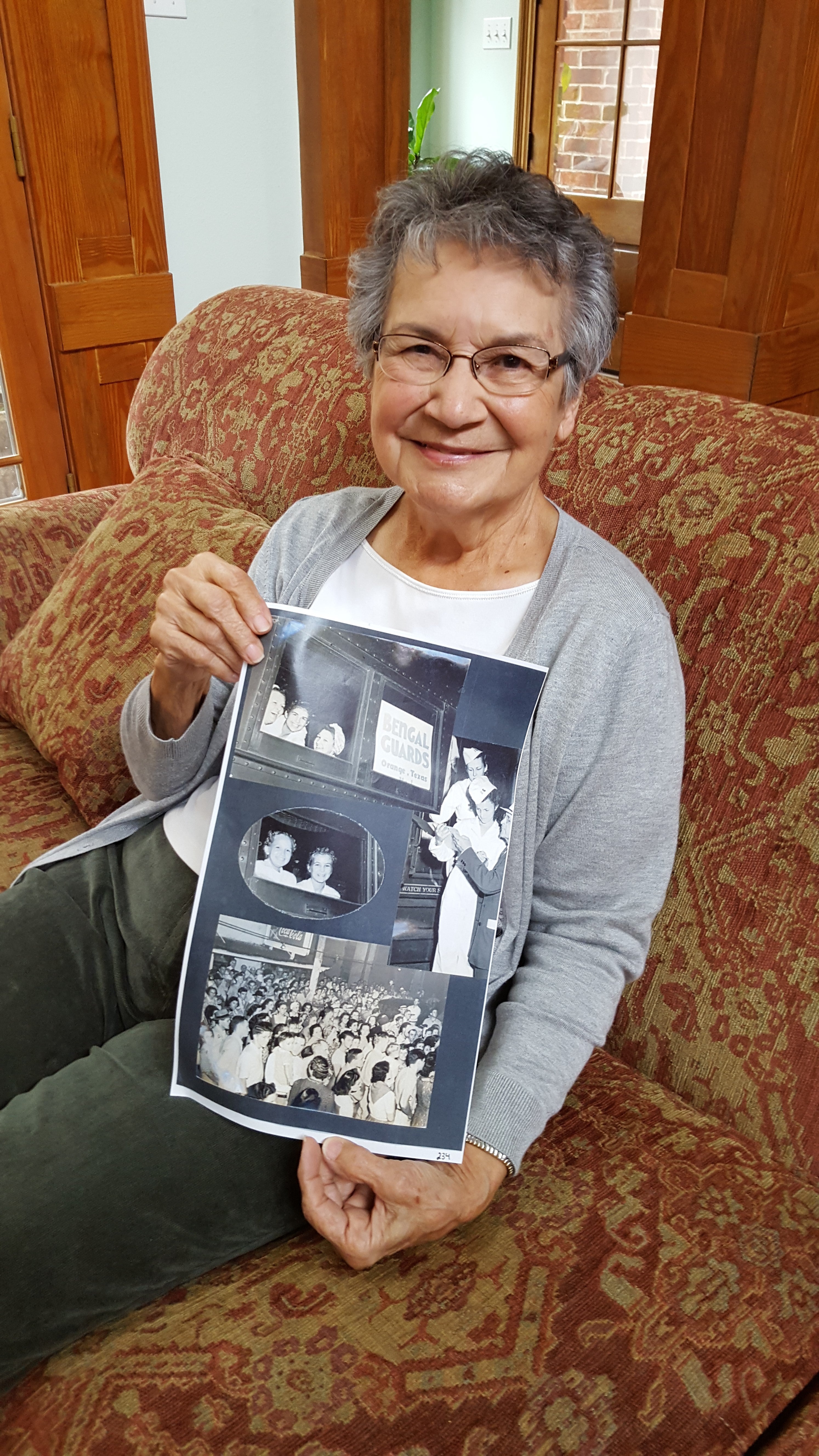

- Martha Bush/The Orange Leader Alexine Adams is holding a picture from when The Guards went to The Chicgoland Music Festival. 5,000 parents and citizens of Orange were at the train station to send the Bengal Guards off on their first big trip. Adams is able to see her parents standing among the crowd in the picture.

By Martha Bush

The Orange Leader

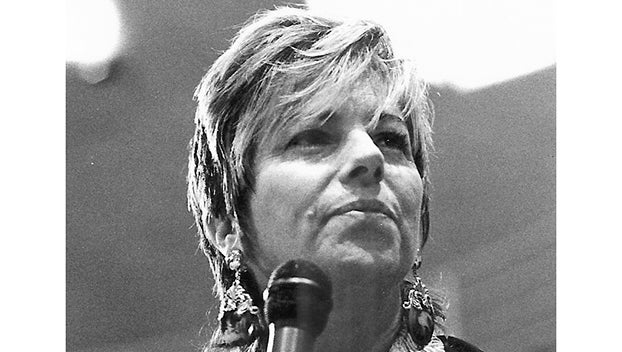

“Ladies and Gentlemen. I give you now America’s own, The Bengal Guards.”

And with that booming announcement coming from Lutcher Stark, founder of the Bengal Guards, over a hundred girls led by outstanding drum majorettes and baton twirlers, would march onto high school football fields in the Golden Triangle, as well as such cities as Chicago, New Orleans, Austin and Waco. Performing to thousands, their formations and military maneuvers were performed at the rate of 175 steps a minute while playing many different types of musical instruments – all of which were provided and funded by Stark.

As a transplant to Texas, I must admit I had been living in Texas quite some time before I heard any mention of the Guards. Perhaps you can relate if you are a transplant to Orange or even a generation that grew up past the time period of their immense popularity between 1935 and 1944.

If so, I invite you to stay with me as Alexine Adams, a former guard, invited me into her home to chat with her about the Bengal Guards. Adams unveils the story of how a group of young ladies living during The Great Depression, not only impacted the city of Orange, but also made their debut on the national stage as a precision marching band. As she tells the story, she speaks with much admiration and gratitude for the man and woman who invested their time and wealth into making it all possible, Lutcher Stark and his wife, Nita.

The story goes that in October of 1935, Lutcher Stark was impressed with the performances of the Red Hussars, a girls’ drum and bugle group in Port Arthur, so he hired their director, Mrs. L.W. Hustmyre, to form a group at Orange High School. To assist Hustmyre with the military drill, Stark hired Louis R. Gay, former director of the Port Arthur American Legion drum and bugle corps.

Their task was to turn a group of average girls into a precision drill unit. He would provide instruments, uniforms and other necessary expenses, as well as arrange for Colonel George Hurt, director of the University of Texas Longhorn Band, to teach them music lessons.

And so it was, after a year of hard work, the guards performed for the first time on October 2, 1936, at the Orange Tigers versus Jasper Bulldogs football game.

That first game triggered the beginning of a succession of football games throughout the Golden Triangle, as well as entertaining at special events. They were invited to perform for ship christenings at the Orange Naval Base, marched in parades too numerous to mention, performed at the Rainbow Bridge Dedication in 1938, and even served as First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt’s honor guard during her visit to Beaumont in 1939, to name a few events.

It wasn’t long before their popularity began to take on momentum as the young girls began receiving invitations to participate in events far beyond the small town of Orange where they had grown up.

For starters, in 1940, they were guests at The Chicagoland Music Festival where Soldier Field audiences totaled 80,000 to 90,000. With pride in her eyes, Adams showed me a picture of the group leaving for Chicago. The Boys band played and 5,000 parents and citizens of Orange gathered for their send-off as they were leaving on the “Bengal Guard Special,” a train chartered by Stark. “That’s my parents standing right down in the corner of this picture,” Adams said.

Accompanying the 124 girls on the train were two trained nurses, two personal maids, three quartermasters, two highway patrolmen, and several chaperones. Following their trip to Chicago, they were featured in Life Magazine and given a three-page photo spread.

Walt Disney could not have made the guards have a more fascinating storybook adventure. As invitations kept pouring in from around the country, they traveled on chartered buses and private trains, stayed in fancy hotels, ate fine meals and wore custom-designed clothes. If they needed a perm in their hair, they got it; if their teeth needed fixing, they were fixed – all of which was funded by Lutcher Stark.

His philosophy was that no child should be excluded – all girls would be treated the same, regardless of economic status.

“Mr. Stark even furnished us with our spending money on our trips,” Adams related. “Here girls, go site-seeing and shopping,” he would say. “And don’t forget to buy something special to take back home to your mama.”

The guards’ “celebrity status” did not come without a price from the girls.

“We worked hard. We practiced five days a week with the exception of the month of July,” Adams emphasized.

At one point in my chat with Adams, she casually mentioned the fact that years ago she heard that Little Cypress High School wanted to start a drill team.

She said out loud to herself: “Well, I can do that!”

And so it was, she formed the Little Cypress Honey Bear Drill Team.

My ears perked up.

“You formed the Honey Bears?” I asked.

Very humbly, she said, “Yes, I had been trained by the best instructors, was taught the importance of discipline and hard work. Now it was time for me to give back to my community the things I had learned from Mr. Stark.”

“Mrs. Adams,” I said. “Do you realize what you learned some 60 years ago and were willing to pass on, you were instrumental in giving my own two girls, Crystal and Heather, a big boost to their self-esteem? We arrived in Orange from New Orleans in 1987, and my daughters needed an outlet in which to relieve their fears of being the “new kid” in town. The Honey Bears Drill Team gave that to them. This transplant to Texas Mama wants to personally thank you.”

“It is a small world,” Adams said with a smile. “That makes me feel like I have made a contribution.”

The years have flown by since The Guards made their first appearance at the Orange Tigers versus Jasper Bulldogs football game. As Adams did, the other girls went on to contribute much to their own communities as a result of the training and education they received from the hands of Lutcher Stark.

The ladies of the Guards maintained a tight-knit bond with one another over the years, holding reunions, reminiscing about their days as a Guard, and most of all being filled with gratitude for what Stark had done for them.

“It was during the Depression and we all had nothing, but Mr. Stark gave us an opportunity by investing in the youth of our community. I was a shy young girl. What he did literally changed my life!”

And now, as their Golden Years have crept up with many being deceased, they wish to make one final contribution to the city of Orange as a remembrance of what “Pop,” as they called Mr. Stark, did for them.

They have set up a memorial sign at West Orange Middle School Campus on Green Avenue in appreciation and reminder of what Lutcher Stark did for the youth of Orange during the worst of times -The Depression.

As our conversation was coming to a close, I asked Mrs. Adams if she had any final words she would like to pass on to others.

Without hesitation, she replied: “If you think you can’t do something, try it anyway. Do your best. Discipline yourself. Share what you have learned. If you can help someone, do it!”

And isn’t that what leaving a legacy is all about?

For a complete history of the Bengal Guards, Alexine Adams wrote an article for the Orange County Historical Society, and it can be found at The Heritage House.