Parent frustrated by years of misdiagnosis

Published 8:57 am Wednesday, July 22, 2015

By Daniel J. Vance MS, LPCC

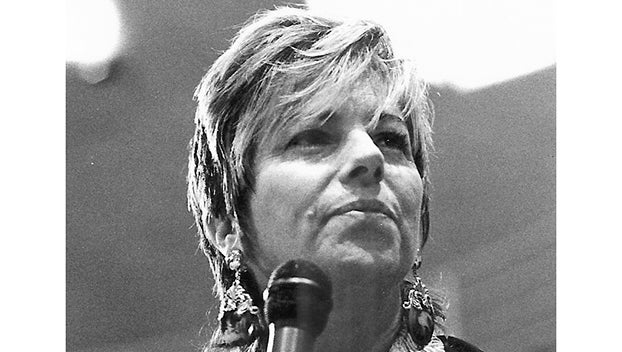

Patricia Stroh of New Bern, North Carolina, has strong advice for parents of children with disabilities: ”You know your child better than anyone. If you feel doctors are wrong or lackadaisical in diagnosing (your child), go somewhere else. Demand results.”

Her son, Derek, was born in 1989 in upstate New York. Within months, he was having trouble sucking, sleeping, and was crying constantly. Doctors found one, then two hernias, and operated. As he aged, one physician after another misdiagnosed Derek, a total of half a dozen times. His correct diagnosis wasn’t discovered until an autopsy after his death at 18, which likely could have been prevented had any doctor along the way diagnosed him correctly.

One doctor said early on nothing was wrong. Another diagnosed Derek at 5 with a form of cerebral palsy, and another with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder when Derek was 7. Then came a mild autism diagnosis at 12 and later a professional decided on pervasive developmental delay.

They were all wrong.

Stroh said Derek had speech, balance, vision, and cognitive problems growing up. “And socially, he had difficulties, such as inappropriate behavior in class,” said 62-year-old Stroh. “He had difficulty with peers. He didn’t understand personal space. He thought it was hysterical, for example, to constantly blow into someone’s ear. He hugged people inappropriately and didn’t understand the repurcussions. He was not allowed nor did anyone want him involved in group sports.” His classmates picked on him.

Yet Derek had another side. He had a good sense of humor and did well in computer science class, Stroh said. He enjoyed skiing, swimming, and chorus. He liked playing the piano.

Derek passed away at 18 from cardiac arrhthymia after playing on a trampoline. He had just had an MRI. Stroh later learned the MRI confirmed Derek was born with periventricular leukomalacia, which the National Institutes of Health defines as “the death of the white matter of the brain due to softening of the brain tissue.” It likely occurred in Derek before or just after his birth.

To chronicle her experiences, Stroh wrote the book, “The ABCDEFG Disorder.”

Had the Strohs known the correct diagnosis earlier, Derek likely would have adjusted better to his condition and his parents would have avoided years of frustration. They also could have explained his condition to Derek’s teachers and peers, and received more emotional support from them.

Facebook: Disabilities By Daniel J. Vance. [Sponsored by Palmer Bus Service and Blue Valley Sod.]